The Single-Agent Trap

Most developers hit the same wall with Claude Code. They start a complex task — refactor an authentication system, migrate a database schema, build a new feature across multiple files — and dump the entire thing into one prompt. The context window fills up, the model starts forgetting earlier instructions, and the output quality degrades in ways that are subtle enough to miss but painful enough to matter.

The fix isn’t a longer context window. It’s splitting the work across multiple agents.

In Part 1, we covered the basics: how Claude Code operates in your terminal, how to structure prompts, how the CLI differs from the chat interface. Now the interesting part starts. Multi-agent workflows and custom skills are where Claude Code goes from “convenient autocomplete” to something that genuinely changes how you architect a development session.

Why Multi-Agent Beats Single-Agent (And When It Doesn’t)

Here’s the counterintuitive thing: spawning a sub-agent with the Task tool doesn’t just help with organization — it actually produces better output per-task. Each agent starts with a fresh context, focused on exactly one job. No leftover state from three prompts ago bleeding into the current task. No attention dilution across a 50,000-token conversation history.

The mental model that works best: think of it like Unix pipes. Each agent does one thing well, passes its result forward, and the orchestrating agent decides what happens next. Claude Code’s Task tool lets you launch specialized sub-agents (Bash, Explore, Plan, general-purpose) that each carry their own context and toolset. The orchestrator sees a summary of what the sub-agent found, not the entire exploration transcript.

But — and this matters — multi-agent workflows have real overhead. Each agent launch takes time, and the coordination logic adds complexity. For a simple “fix this typo” or “add a log statement,” spinning up a sub-agent is overkill. The threshold where multi-agent starts paying off is roughly when you’d otherwise need to scroll back through your conversation to remember what you were doing. Three or more files, two or more conceptually distinct steps, any task where you’d naturally think “let me handle X first, then Y” — that’s agent territory.

Designing Agent Pipelines That Actually Work

The pattern that’s proven most reliable in practice looks like this:

- Explore agent gathers context (codebase structure, existing patterns, relevant files)

- Plan agent designs the approach based on that context

- Bash/general-purpose agents execute the implementation in parallel where possible

- Review agent (often another general-purpose agent) checks the result

Here’s what a real orchestration looks like. Say you want to add a new API endpoint with tests. Instead of one massive prompt, you’d structure it as a pipeline where each agent has a focused job:

# Pseudocode for the mental model — this is what happens

# inside Claude Code when you structure your CLAUDE.md correctly

# Step 1: Explore existing patterns

explore_result = task(

agent="Explore",

prompt="Find all API endpoint definitions and their test files. "

"What patterns do they follow for routing, validation, and error handling?"

)

# Step 2: Plan the implementation

plan_result = task(

agent="Plan",

prompt=f"Based on these existing patterns: {explore_result}\n"

f"Design the implementation for a new /api/metrics endpoint "

f"that returns user activity data with pagination."

)

# Step 3: Execute — these can run in parallel

impl_result = task(

agent="general-purpose",

prompt=f"Implement the endpoint following this plan: {plan_result}"

)

test_result = task(

agent="general-purpose",

prompt=f"Write tests for the endpoint following this plan: {plan_result}"

)

The key insight isn’t the pipeline itself — it’s that each agent receives only the context it needs. The Explore agent doesn’t need to know about your implementation plan. The test-writing agent doesn’t need the full exploration transcript. This selective context passing is what keeps quality high as task complexity grows.

Parallel Execution

Claude Code can launch multiple sub-agents simultaneously when there are no dependencies between them. In the example above, writing the implementation and writing the tests can happen in parallel once the plan exists. This isn’t just a speed optimization — it also means neither agent’s context is polluted by the other’s work-in-progress.

In practice, you trigger parallel execution by making multiple Task tool calls in a single message. The system handles the rest. I’ve seen this cut total wall-clock time by 30-40% on tasks that have naturally parallelizable components, though your mileage will vary depending on the specific workload.

Custom Skills: Teaching Claude Code New Tricks

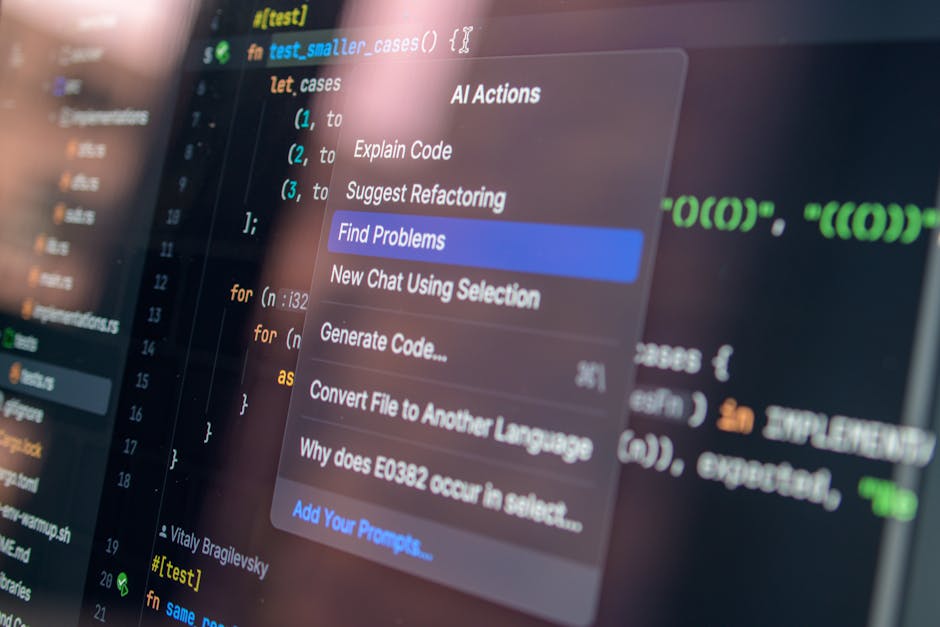

Skills are where Claude Code gets genuinely extensible. A skill is essentially a packaged instruction set that Claude Code can invoke by name — think of it like a shell alias, but for AI behavior rather than command shortcuts.

The .claude/ directory in your project root is where these live. You’ve already seen CLAUDE.md (the project-level instruction file from Part 1), but the real power comes from the agents directory and custom command definitions.

Here’s a concrete example. This blog’s auto-posting system uses specialized agents defined in .claude/agents/:

# .claude/agents/code-reviewer.md

You are a code reviewer for a WordPress automation system.

Check for:

- SQL injection in any WordPress API calls

- Credential exposure in config handling

- Memory issues (server has only 1GB RAM)

- Python subprocess calls that might hang

Flag severity as CRITICAL / WARNING / INFO.

CRITICAL issues must be fixed before deployment.

# .claude/agents/seo-optimizer.md

Review the post publishing logic for SEO issues:

- Meta description length (140-155 chars)

- Open Graph tags present and correct

- Slug format (lowercase, hyphenated, under 60 chars)

- Schema.org structured data validity

- hreflang tags for internationalization

Output specific fixes, not general advice.

When you invoke these through the Task tool, each agent inherits the project context from CLAUDE.md but adds its own specialized lens. The code reviewer doesn’t care about SEO. The SEO optimizer doesn’t care about memory leaks. This separation of concerns mirrors how real engineering teams work — you don’t ask your security auditor to also check your meta tags.

The CLAUDE.md Hierarchy

Claude Code reads instructions from multiple levels, and understanding the precedence matters more than most people realize:

~/.claude/CLAUDE.md— user-level defaults (your personal coding style, preferred tools)project/.claude/CLAUDE.md— project-level rules (architecture, deployment, coding standards)- Agent-specific

.mdfiles — specialized behavior for sub-agents

Project-level instructions override user-level ones when they conflict. Agent instructions layer on top of both. This hierarchy lets you set global preferences (“always use type hints in Python”) while still having project-specific overrides (“this legacy codebase uses no type hints, don’t add them”).

One thing the docs don’t make obvious: the CLAUDE.md content gets injected into every agent’s system context as a <system-reminder>. This means your project instructions travel with your agents automatically. You don’t need to repeat “this is a WordPress automation project running on 1GB RAM” in every agent definition — it’s already there.

Practical Patterns That Survive Contact With Reality

Here’s where theory meets the messy real world. A few patterns that have held up after weeks of daily use:

The Review Gate pattern. After any code change, before deployment, run a review agent. This sounds obvious, but the difference is making it mandatory in your workflow rather than optional. In the auto-poster’s CLAUDE.md, the rule is explicit: “Run agent review after code changes, before deployment. Fix all CRITICAL issues found by agents before deployment.” Having it written in the project instructions means Claude Code enforces it on itself — it won’t skip the review step even if you forget to ask for it. The compliance rate isn’t perfect (my best guess is around 90% when the instruction is clearly written), but it’s better than relying on human memory.

The Explore-Before-Edit pattern. Never let an agent edit code it hasn’t read. This seems like common sense, but it’s easy to violate when you’re moving fast. The Explore agent type exists specifically for this — it has read access to the codebase but cannot write or edit files. Use it to gather context, then pass that context to an editing agent. The information asymmetry is the point: the explorer finds relevant code, the editor changes it, and neither steps on the other’s work.

The Fallback Chain pattern. Real systems fail. Models hit rate limits, context windows overflow, APIs return errors. Building fallback logic into your agent workflow is essential. Here’s a real example from the auto-poster:

def claude_request(prompt):

"""Try opus first, fall back to sonnet, skip if both exhausted."""

models = ["opus", "sonnet"]

for model in models:

try:

result = subprocess.run(

["claude", "-p", prompt, "--model", model],

capture_output=True, text=True, timeout=300

)

if result.returncode == 0:

return result.stdout.strip()

# Check for usage exhaustion specifically

if "usage" in result.stderr.lower() and "exhausted" in result.stderr.lower():

continue # try next model

# Other errors — don't retry, something else is wrong

raise RuntimeError(f"Claude {model} failed: {result.stderr}")

except subprocess.TimeoutExpired:

# This shouldn't happen with a 5-minute timeout, but...

continue

raise UsageExhaustedError("All models exhausted")

Notice the edge case guard on timeout — with a 300-second limit, timeouts should be rare, but the auto-poster runs on a 1GB ARM instance where anything can happen. The comment “this shouldn’t happen but…” is the kind of defensive code that saves you at 3 AM when the cron job fails silently.

When Agents Talk Past Each Other

The hardest bug to diagnose in multi-agent workflows is context mismatch. Agent A explores the codebase and finds that authentication uses JWT. Agent B receives a summary that says “uses token-based auth.” Agent B then implements session-based auth because “token-based” was ambiguous. The fix is being painfully specific in the context you pass between agents. Not “uses token-based auth” but “uses JWT tokens stored in httpOnly cookies, validated by middleware in src/auth/verify.ts, with refresh tokens in a Redis store.”

I’m not entirely sure why, but terse context summaries between agents produce worse results than you’d expect from the token savings. My working theory is that the receiving agent fills in ambiguity with its priors rather than asking for clarification, and its priors might not match your codebase. Verbose inter-agent context is cheap insurance.

The Coordination Cost Formula

There’s a rough mental math for when to add another agent to your pipeline. If we think of total task quality as a function of per-agent focus and coordination overhead , something like:

where is the number of agents and weights how expensive your coordination is. Each additional agent increases total focus (fresh context, specialized instructions) but also adds coordination cost (context passing, result aggregation, potential mismatch). For on a well-defined task, the focus gains dominate. Beyond that, coordination overhead starts eating into quality. The sweet spot for most development tasks seems to be 2-4 agents.

The coordination cost grows roughly as in the worst case (every agent needs to know about every other agent’s output), but in practice, pipeline architectures keep it closer to since each agent only talks to its neighbors. This is why pipeline > mesh for agent workflows.

And if you’re thinking “this sounds like microservices vs monolith” — yes, the same tradeoffs apply. Small, focused agents are easier to reason about individually but harder to coordinate. One big agent is simpler to manage but degrades unpredictably as complexity grows.

Building Your Own Agent Definitions

The syntax for agent definitions is just Markdown — no special schema, no YAML configuration, no build step. Drop a .md file in .claude/agents/ and it’s available as a specialized agent. The content should describe the agent’s role, what it should check or produce, and what severity levels mean in its domain.

A few things I’d do differently if starting from scratch:

First, make agent outputs structured. Instead of “check for issues and report them,” specify “output a JSON array with fields: file, line, severity, description, suggested_fix.” Structured output from review agents makes it trivial to pipe results into the next step. Free-form prose reports are harder to act on programmatically.

Second, include negative examples. Tell the agent what NOT to flag. “Don’t flag missing type hints in test files” or “Ignore CSS specificity issues in admin-only pages.” Without negative examples, review agents tend toward false positives, and false positive fatigue kills the whole workflow faster than missing real issues.

Third, version your agent definitions alongside your code. When your architecture changes, your review criteria should change too. An agent definition that checks for “Redux state management patterns” is useless after you migrate to Zustand. This sounds obvious but I’ve seen agent definitions go stale within weeks.

What’s Actually Different About This

Why not just use a CI pipeline or a linter for all this? Fair question. The difference is that agent-based review operates at the semantic level, not the syntactic level. A linter can catch unused imports. A review agent can catch “this function makes an API call inside a loop and will hammer the rate limit.” The gap between what static analysis catches and what a focused AI agent catches is where the value lives — the logic errors, the architectural mismatches, the performance anti-patterns that pass every lint rule.

That said, agents aren’t a replacement for linters and type checkers. They’re a different layer. Run mypy and eslint first, then run your agent review on the output that passes static analysis. The agent’s attention is better spent on semantic issues when syntactic issues are already resolved. The total error detection rate follows something like:

Each independent layer multiplicatively reduces the probability of an issue slipping through. Stacking them is the whole point.

What I’d Tackle Differently Next Time

If I were rebuilding the agent pipeline from scratch, I’d invest more upfront in inter-agent contracts — explicit schemas for what each agent produces and consumes. Right now, the auto-poster’s agents communicate through natural language summaries, which works but introduces the ambiguity problem described earlier. Something like JSON Schema for agent outputs would eliminate an entire class of coordination bugs.

I’d also experiment with feedback loops — having downstream agents report quality issues back to upstream agents. Currently, the pipeline is strictly feed-forward: explore → plan → implement → review. But what if the review agent could flag that the plan missed an edge case, and the plan agent could revise? Claude Code doesn’t natively support this kind of iterative refinement between agents (each agent invocation is independent), but you could build it at the orchestration level with a retry loop.

The honest truth is that multi-agent workflows in Claude Code are still early. The tooling works, the patterns are emerging, but we’re probably a year away from this feeling as natural as git branch and git merge. The developers who figure out reliable agent coordination patterns now will have a serious advantage when the tooling matures.

In Part 3, we’ll look at what it takes to run Claude Code in production — cron jobs, error recovery, monitoring, and the operational reality of an AI system that publishes content autonomously. The gap between “works on my machine” and “runs reliably at 3 AM on a 1GB server” is wider than most people expect.

Did you find this helpful?

☕ Buy me a coffee

Leave a Reply