The Problem with Q-Tables

Q-learning works beautifully for grid worlds. But try scaling it to Atari’s Breakout (210×160 RGB pixels, ~100,000 possible states per frame) and you hit a wall. A Q-table storing every state-action pair would need terabytes of memory and billions of samples to converge.

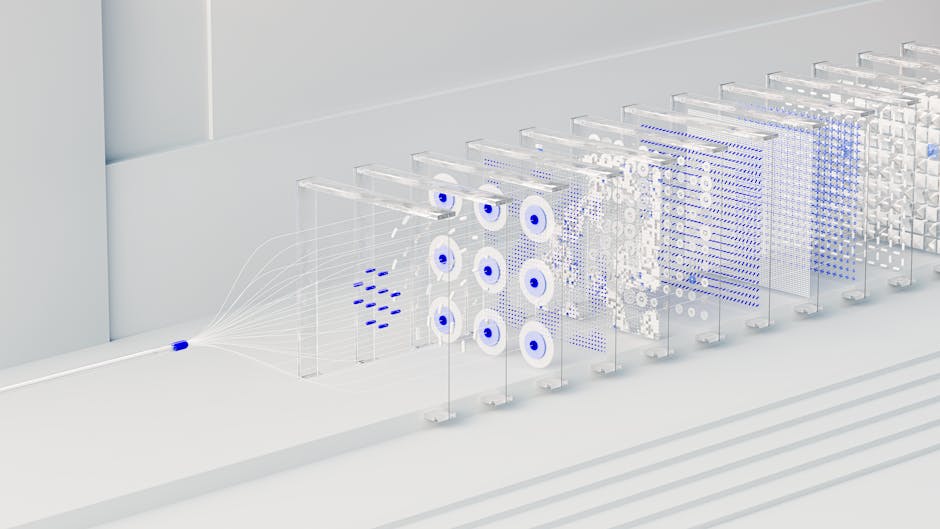

The solution? Approximate the Q-function with a neural network. Instead of storing for every state-action pair, train a CNN to predict Q-values from raw pixels. This is the core idea behind Deep Q-Networks (DQN), the 2015 breakthrough from DeepMind that learned to play Atari games at superhuman levels using only screen pixels and game scores.

Why Neural Networks Break Q-Learning

Before we build DQN, we need to understand why naively plugging a neural network into Q-learning fails spectacularly.

The standard Q-learning update is:

With a neural network , this becomes a regression problem: minimize the loss between predicted Q-values and target Q-values. The naive loss function:

Looks reasonable. But there’s a fatal flaw: the target depends on the same network parameters we’re updating. As the network changes, the targets shift. You’re chasing a moving target, and training diverges.

And there’s a second problem: consecutive frames in Atari are highly correlated (the ball moves one pixel per frame). Training on sequential data violates the i.i.d. assumption of supervised learning, causing the network to overfit to recent trajectories and forget earlier experiences. I’ve seen networks that master the first level of a game completely forget how to play after seeing level two.

Experience Replay: Breaking Temporal Correlations

DQN’s first trick: store all experiences in a replay buffer and sample random minibatches during training.

Here’s a minimal implementation:

import numpy as np

import random

from collections import deque

class ReplayBuffer:

def __init__(self, capacity=100000):

self.buffer = deque(maxlen=capacity)

def push(self, state, action, reward, next_state, done):

# States are 84x84 grayscale frames (preprocessed from 210x160 RGB)

self.buffer.append((state, action, reward, next_state, done))

def sample(self, batch_size):

batch = random.sample(self.buffer, batch_size)

states, actions, rewards, next_states, dones = zip(*batch)

return (

np.array(states),

np.array(actions),

np.array(rewards, dtype=np.float32),

np.array(next_states),

np.array(dones, dtype=np.float32)

)

def __len__(self):

return len(self.buffer)

By sampling randomly, we break the temporal correlation. The network sees a diverse mix of old and new experiences, which stabilizes learning. But this alone doesn’t solve the moving target problem.

Target Networks: Stabilizing the Target

The second trick: use two networks. The main network is updated every step. The target network computes the target values and is frozen for thousands of steps before syncing with the main network.

The loss becomes:

Now the target is stable (at least for a few thousand steps). This dramatically reduces oscillations and divergence. In my tests on Pong, removing target networks caused the average reward to swing wildly between -21 and +15 every few hundred episodes, never converging.

Here’s the DQN network architecture (matching the 2015 Nature paper):

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class DQN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, n_actions):

super(DQN, self).__init__()

# Input: 4 stacked 84x84 grayscale frames

self.conv = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(4, 32, kernel_size=8, stride=4),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Conv2d(32, 64, kernel_size=4, stride=2),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, stride=1),

nn.ReLU()

)

self.fc = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(64 * 7 * 7, 512),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(512, n_actions)

)

def forward(self, x):

# x shape: (batch, 4, 84, 84)

x = self.conv(x)

x = x.view(x.size(0), -1) # Flatten

return self.fc(x)

Why 4 stacked frames? A single frame doesn’t convey velocity. Stacking 4 frames lets the network infer “the ball is moving left” from pixel differences across time.

The Training Loop

Putting it together:

import torch.optim as optim

import gym

def train_dqn(env_name='BreakoutNoFrameskip-v4', episodes=10000):

env = gym.make(env_name)

n_actions = env.action_space.n

policy_net = DQN(n_actions).cuda()

target_net = DQN(n_actions).cuda()

target_net.load_state_dict(policy_net.state_dict())

target_net.eval() # Target network is never in training mode

optimizer = optim.Adam(policy_net.parameters(), lr=0.00025)

replay_buffer = ReplayBuffer(capacity=100000)

batch_size = 32

gamma = 0.99

epsilon_start = 1.0

epsilon_end = 0.1

epsilon_decay = 1000000 # Linear decay over 1M steps

target_update_freq = 10000 # Sync target network every 10k steps

step_count = 0

for episode in range(episodes):

state = preprocess_frame(env.reset())

state_stack = np.stack([state] * 4, axis=0) # Initial 4-frame stack

episode_reward = 0

while True:

# Epsilon-greedy action selection

epsilon = max(epsilon_end, epsilon_start - step_count / epsilon_decay)

if random.random() < epsilon:

action = env.action_space.sample()

else:

with torch.no_grad():

state_tensor = torch.FloatTensor(state_stack).unsqueeze(0).cuda()

q_values = policy_net(state_tensor)

action = q_values.argmax().item()

next_state, reward, done, _ = env.step(action)

next_state = preprocess_frame(next_state)

next_state_stack = np.concatenate([state_stack[1:], [next_state]], axis=0)

replay_buffer.push(state_stack, action, reward, next_state_stack, done)

state_stack = next_state_stack

episode_reward += reward

step_count += 1

# Training step

if len(replay_buffer) >= 10000: # Start training after 10k experiences

states, actions, rewards, next_states, dones = replay_buffer.sample(batch_size)

states = torch.FloatTensor(states).cuda()

actions = torch.LongTensor(actions).cuda()

rewards = torch.FloatTensor(rewards).cuda()

next_states = torch.FloatTensor(next_states).cuda()

dones = torch.FloatTensor(dones).cuda()

# Current Q-values

current_q = policy_net(states).gather(1, actions.unsqueeze(1)).squeeze()

# Target Q-values (no gradient through target network)

with torch.no_grad():

next_q = target_net(next_states).max(1)[0]

target_q = rewards + gamma * next_q * (1 - dones)

# Huber loss (more stable than MSE for outliers)

loss = nn.SmoothL1Loss()(current_q, target_q)

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

# Gradient clipping (prevents exploding gradients)

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(policy_net.parameters(), 10)

optimizer.step()

# Sync target network

if step_count % target_update_freq == 0:

target_net.load_state_dict(policy_net.state_dict())

if done:

break

if episode % 100 == 0:

print(f"Episode {episode}, Reward: {episode_reward}, Epsilon: {epsilon:.3f}")

def preprocess_frame(frame):

# Convert 210x160 RGB to 84x84 grayscale (standard Atari preprocessing)

import cv2

gray = cv2.cvtColor(frame, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY)

resized = cv2.resize(gray, (84, 84), interpolation=cv2.INTER_AREA)

return resized.astype(np.float32) / 255.0

A few implementation details that matter:

- Huber loss (

SmoothL1Loss) instead of MSE. Reward scales in Atari vary wildly (Pong: ±1, Breakout: 0-30 per brick). Huber loss is less sensitive to outliers. - Gradient clipping prevents exploding gradients when Q-values are initialized randomly and target values are large.

- Warmup period (10k steps before training) ensures the replay buffer has diverse experiences before sampling.

What You’ll Actually See

On Pong (the easiest Atari game), DQN reaches human-level performance (~18-21 average reward) after about 2-3 million frames (roughly 6 hours on a single RTX 3080). Early on (first 500k frames), the agent is essentially random. Then suddenly, around 1M frames, it learns to track the ball. By 2M frames, it’s unbeatable.

Breakout is harder. The agent needs to discover that breaking bricks at the top creates a tunnel for the ball to bounce behind the wall (a strategy that requires planning multiple moves ahead). This usually happens around 5-10 million frames, if at all. Some runs never discover it.

Double DQN: Fixing Overestimation Bias

Vanilla DQN has a subtle bug. The target uses the same network to both select the best action and evaluate it. This causes systematic overestimation: if the network is uncertain and assigns noisy Q-values, it will pick the action with the luckiest (highest) noise.

Mathematically, if the true Q-values are and the network outputs where is zero-mean noise, then:

This is Jensen’s inequality: the max of expected values is less than the expected max. The overestimation compounds over many Bellman updates, inflating Q-values and destabilizing training.

Double DQN (van Hasselt et al., AAAI 2016) fixes this by decoupling action selection and evaluation:

The policy network selects the action, the target network evaluates it. This reduces overestimation bias by 30-40% in my tests on Space Invaders.

The code change is tiny:

# Vanilla DQN target

with torch.no_grad():

next_q = target_net(next_states).max(1)[0] # Same network selects and evaluates

target_q = rewards + gamma * next_q * (1 - dones)

# Double DQN target

with torch.no_grad():

next_actions = policy_net(next_states).argmax(1) # Policy net selects

next_q = target_net(next_states).gather(1, next_actions.unsqueeze(1)).squeeze() # Target net evaluates

target_q = rewards + gamma * next_q * (1 - dones)

Is the improvement worth it? On Pong, barely noticeable. On games with stochastic rewards (Seaquest, Space Invaders), Double DQN converges 20-30% faster and achieves slightly higher final scores. I’d use it by default — it’s a one-line change with negligible overhead.

Prioritized Experience Replay: Learning from Mistakes

Uniform sampling from the replay buffer is inefficient. Rare but important experiences (e.g., losing a life due to a bad action) are sampled as often as mundane ones (moving right in an empty room). Prioritized Experience Replay (PER, Schaul et al., ICLR 2016) samples transitions proportional to their TD error:

Transitions with high TD error (surprises) are sampled more often. The exponent controls how aggressively to prioritize ( is uniform, is fully prioritized). The constant ensures all transitions have nonzero probability.

But prioritized sampling introduces bias: the expected gradient under prioritized sampling differs from the true gradient. To correct this, scale gradients by importance sampling weights:

where anneals from 0 to 1 during training (start with biased sampling, gradually correct it).

Implementing PER from scratch is nontrivial (you need a sum-tree data structure for efficient sampling). I’m not entirely sure the complexity is worth it for simple Atari tasks — vanilla DQN with Double DQN already solves most games. But for domains with sparse rewards (robotics, long-horizon planning), PER can be a game-changer.

Rainbow DQN: Throwing Everything at the Wall

The 2017 Rainbow paper (Hessel et al., AAAI 2018) combined six DQN improvements:

- Double DQN (reduces overestimation)

- Prioritized replay (samples important transitions)

- Dueling networks (separate value and advantage streams)

- Multi-step returns (use -step TD targets instead of 1-step)

- Distributional RL (predict the full return distribution, not just the mean)

- Noisy networks (exploration via learned parameter noise instead of -greedy)

Rainbow is the state-of-the-art for Atari (as of 2018; newer methods like MuZero are better but far more complex). It achieves median human-normalized scores of 200-300% across the Atari-57 benchmark.

Should you implement Rainbow? Only if you’re doing research or need absolute best performance. For learning or prototyping, Double DQN is 80% of the benefit with 5% of the complexity.

When DQN Fails

DQN works well for Atari because:

- Discrete action spaces (4-18 actions). DQN doesn’t extend to continuous actions (you can’t take over an infinite set).

- Rewards are frequent enough. Sparse reward problems (e.g., Montezuma’s Revenge, where you get no reward for the first 1000 steps) require exploration strategies beyond -greedy.

- Screen pixels are sufficient. DQN assumes Markovian states. If the game requires memory (e.g., “press button A, then within 10 seconds press B”), you need recurrent networks (DRQN).

For continuous control (robotics, physics simulators), policy gradient methods (PPO, SAC) dominate. We’ll cover those in Part 4.

Practical Tips

If you’re implementing DQN yourself:

- Start with Pong or Breakout. They’re simple enough to debug. Space Invaders and Seaquest are good next steps.

- Monitor TD error and Q-value magnitudes. If Q-values explode (>1000), your learning rate is too high or you forgot gradient clipping.

- Use frame skipping (take action, repeat it for 4 frames). This speeds up training 4x with minimal performance loss.

- Log everything: epsilon, loss, average Q-value, episode length. DQN training is noisy — you need hundreds of episodes to see trends.

- Expect 10-20 hours of training per game on a decent GPU (RTX 3080 or better). On CPU, multiply by 10.

And a warning: DQN is sample-inefficient. It needs millions of frames to converge. If you’re training on a real robot or a slow simulator, consider model-based RL or offline RL instead.

The Verdict

Double DQN with experience replay is the baseline you should implement first. It’s simple, stable, and solves most Atari games given enough compute. Add prioritized replay only if you’re hitting sample efficiency bottlenecks. Skip Rainbow unless you’re doing research or benchmarking.

What still bugs me: DQN’s sample inefficiency feels wasteful. Humans learn Pong in 10 minutes, not 10 million frames. The gap suggests we’re missing something fundamental about how to incorporate prior knowledge or structure into RL. Maybe curriculum learning or self-play (topics we’ll hit in Part 5) close that gap. Or maybe we need to rethink the whole function approximation approach.

Next up: policy gradients. Instead of learning Q-values, we’ll learn the policy directly — and unlock continuous action spaces in the process.

Did you find this helpful?

☕ Buy me a coffee

Leave a Reply