The Promise vs. The Reality

Most smart factory demos show a pristine production line with AI detecting defects at superhuman speed, predicting failures weeks in advance, and optimizing schedules in real-time. Then you visit an actual factory and see a single camera bolted to a conveyor belt, running a model that flags every third product as defective because someone changed the lighting last week.

The gap between the vision and what actually works is massive. Not because the technology isn’t ready—computer vision models can absolutely detect hairline cracks in metal parts, and time series forecasting can predict bearing failures. But because integrating AI into a factory that’s been running the same way for 20 years involves problems that have nothing to do with model accuracy.

Let’s talk about what a smart factory really is, where AI fits, and why this is harder than it looks.

What Makes a Factory “Smart”?

The textbook definition involves buzzwords like “cyber-physical systems” and “Industry 4.0.” Practically speaking, a smart factory uses sensors, data, and automation to make better decisions faster than humans can. The “smart” part isn’t just about having fancy equipment—it’s about closing the feedback loop.

Traditional factory: a machine breaks, someone notices, maintenance shows up hours later, production stops.

Smart factory: vibration sensors detect anomalous patterns, the system predicts failure in 48 hours, maintenance schedules a swap during the next planned downtime, production continues uninterrupted.

That prediction step? That’s where AI comes in. But before you can predict anything, you need data. And before you can collect useful data, you need to know what matters.

Most factories weren’t designed with AI in mind. The equipment might be 15 years old. The PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers) running the assembly line might not even have network connectivity. Getting clean, timestamped sensor data out of a legacy system can take months of work before you write a single line of ML code.

The AI Stack in Manufacturing

When people say “AI in factories,” they’re usually talking about one of four things:

Computer vision for quality control. A camera captures images of products as they move down the line. A convolutional neural network (CNN) trained on thousands of labeled examples classifies each item as pass/fail or detects specific defect types. This is probably the most common AI application in manufacturing today because the ROI is obvious—catching defects before they reach customers saves money and reputation.

But here’s the catch: training data is expensive. If your factory produces custom parts in small batches, you might not have enough examples of each defect type to train a robust model. Transfer learning helps (start with a pretrained ImageNet model and fine-tune on your domain), but you still need hundreds of labeled images per defect class. And if the product changes every few months, you’re retraining constantly.

Predictive maintenance (PdM). Sensors on motors, pumps, bearings, etc. record vibration, temperature, current draw, acoustic emissions—whatever signals correlate with failure. A model (often gradient boosting or an LSTM network for time series) learns normal operating patterns and flags anomalies. The goal is to predict “this bearing will fail in N hours” with enough lead time to schedule maintenance.

The math here often involves survival analysis. If you model time-to-failure as a Weibull distribution, the hazard function is:

where is the shape parameter and is the scale. But real factory equipment doesn’t follow neat parametric distributions. That’s why ML models (trained on historical failure data) often outperform traditional reliability equations.

The tricky part? Labels. You need past examples of failures, ideally with sensor data leading up to the event. If your equipment is reliable (which is good!), you don’t have many failures to learn from. Some teams inject synthetic faults or use simulation, but that introduces domain shift.

Anomaly detection on production lines. This overlaps with PdM but focuses on process quality rather than equipment health. If a heating element in an injection molding machine drifts out of spec, the parts coming off the line might still look fine visually but fail stress tests later. An autoencoder trained on normal operating conditions can flag subtle deviations in sensor readings before they cause defects.

The loss function for a simple autoencoder is reconstruction error:

where is the input (sensor readings at time ) and is the reconstruction. High reconstruction error means the input doesn’t match the learned “normal” patterns. But choosing the threshold for what counts as an anomaly is more art than science—you’re trading off false positives (unnecessary alerts) against false negatives (missed issues).

Production scheduling and optimization. This is where reinforcement learning (RL) starts to shine. A factory floor has dozens of variables: machine availability, order priorities, material constraints, energy costs (which vary by time of day). An RL agent can learn a scheduling policy that maximizes throughput or minimizes cost by simulating thousands of scenarios.

The reward function might look like:

where are weights that encode business priorities. The agent learns a policy that maps states (current machine status, pending orders) to actions (schedule job X on machine Y).

But here’s the problem: factories aren’t static environments. A machine that was working fine yesterday might be down for maintenance today. Customer orders change. An RL agent trained in simulation will fail hard when reality diverges from the model. You need robust sim-to-real transfer, which is still an active research area.

Why Edge AI Matters (and When It Doesn’t)

A lot of smart factory vendors push “edge AI”—running models on local hardware near the production line instead of sending data to the cloud. The pitch is lower latency, better privacy, and resilience to network outages.

For quality control on a high-speed line (say, inspecting 100 bottles per second), edge makes sense. You can’t afford the round-trip time to a cloud API. A Jetson Nano or similar edge device running a quantized CNN can do inference in milliseconds.

But for predictive maintenance, where you’re analyzing vibration spectra over hours or days? Cloud is fine. The extra 50ms of latency doesn’t matter. And cloud gives you more compute for retraining, easier model updates, and centralized monitoring across multiple factories.

I’d pick edge when latency is critical (real-time control loops, vision inspection) and cloud for everything else (analytics, retraining, dashboards). The trend of trying to cram every model onto edge hardware feels more like vendor positioning than technical necessity.

The Data Pipeline Problem

Here’s something that surprised me early on: the hardest part of deploying AI in a factory isn’t the model—it’s the data pipeline. You need:

- Reliable sensor data collection. Sensors fail. They drift. They report garbage when someone bumps a cable. You need validation logic, outlier detection, and fallback strategies.

- Time synchronization. If you’re correlating vibration data from sensor A with temperature from sensor B, their timestamps better align. A 1-second offset can ruin your features.

- Feature engineering. Raw sensor readings (e.g., accelerometer voltage) aren’t useful. You need derived features: FFT to get frequency components, rolling statistics (mean, std over a window), rate of change. This is where domain expertise matters more than ML chops.

- Labeling. For supervised learning, you need ground truth. Who decides if a defect is “minor” vs “major”? How do you encode that consistently across shifts and operators?

Most ML tutorials skip this. They give you a clean CSV with features already extracted. Real factories give you terabytes of unlabeled, noisy, asynchronous sensor streams.

A Minimal Example: Vibration-Based Anomaly Detection

Let’s say you want to detect anomalies in a motor’s vibration. You have a 3-axis accelerometer sampling at 1 kHz. Here’s a sketch of what the pipeline might look like:

import numpy as np

from scipy.fft import rfft, rfftfreq

from sklearn.ensemble import IsolationForest

def extract_features(accel_data, fs=1000, window_sec=1):

"""

accel_data: (N, 3) array of x,y,z accelerometer readings

fs: sampling frequency

Returns: feature vector for anomaly detection

"""

window = int(fs * window_sec)

if len(accel_data) < window:

# Edge case: not enough data yet

return None

# Use last 'window' samples

seg = accel_data[-window:]

# Time-domain features

rms = np.sqrt(np.mean(seg**2, axis=0)) # RMS per axis

peak = np.max(np.abs(seg), axis=0)

kurtosis = np.mean((seg - seg.mean(axis=0))**4, axis=0) / (seg.std(axis=0)**4 + 1e-8)

# Frequency-domain: get dominant frequencies

fft_mag = np.abs(rfft(seg[:, 0])) # Just x-axis for simplicity

freqs = rfftfreq(window, 1/fs)

dominant_freq = freqs[np.argmax(fft_mag)]

# Concatenate all features

features = np.hstack([rms, peak, kurtosis, [dominant_freq]])

return features

# Simulate normal operation data (you'd load real historical data here)

np.random.seed(42)

normal_data = []

for _ in range(500):

# Normal vibration: low amplitude, consistent frequency

t = np.linspace(0, 1, 1000)

signal = 0.1 * np.sin(2*np.pi*60*t) # 60 Hz dominant

signal += 0.02 * np.random.randn(1000) # noise

accel = np.column_stack([signal, signal*0.8, signal*0.6])

feats = extract_features(accel)

if feats is not None:

normal_data.append(feats)

X_train = np.array(normal_data)

# Train Isolation Forest (unsupervised anomaly detector)

model = IsolationForest(contamination=0.05, random_state=42)

model.fit(X_train)

print(f"Trained on {len(X_train)} normal samples")

print(f"Feature dim: {X_train.shape[1]}")

# Test on an anomalous case (higher amplitude, different freq)

t = np.linspace(0, 1, 1000)

anom_signal = 0.5 * np.sin(2*np.pi*120*t) + 0.1 * np.random.randn(1000)

anom_accel = np.column_stack([anom_signal, anom_signal*0.8, anom_signal*0.6])

anom_feats = extract_features(anom_accel)

score = model.decision_function([anom_feats])[0]

pred = model.predict([anom_feats])[0]

print(f"Anomaly score: {score:.3f} (negative = more anomalous)")

print(f"Prediction: {'ANOMALY' if pred == -1 else 'NORMAL'}")

Running this (on Python 3.11, numpy 1.24, scikit-learn 1.3), I get:

Trained on 500 normal samples

Feature dim: 10

Anomaly score: -0.142 (negative = more anomalous)

Prediction: ANOMALY

The Isolation Forest correctly flags the high-amplitude, off-frequency signal as anomalous. In practice, you’d tune the contamination parameter based on how often you expect real anomalies (5% is a guess here—could be 1%, could be 10%). You’d also need to handle edge cases: what if the accelerometer saturates? What if you get a burst of NaN values because someone unplugged a cable?

This is a toy example, but it shows the structure: collect raw data, extract domain-relevant features, train an unsupervised model (since labeled failures are rare), set a threshold, deploy. The hard parts are feature engineering (knowing that RMS and kurtosis matter for vibration) and choosing the threshold (too sensitive = alert fatigue, too lenient = missed failures).

Digital Twins: The Hype vs. The Reality

You’ve probably heard “digital twin” thrown around. The idea is to create a virtual replica of your factory (or a specific machine) that mirrors the real system in real-time. Sensors feed data into the simulation, which can then predict what happens if you change a parameter, test maintenance scenarios, or optimize schedules without touching the physical line.

In theory, this is powerful. In practice, building an accurate digital twin is brutally hard. You need:

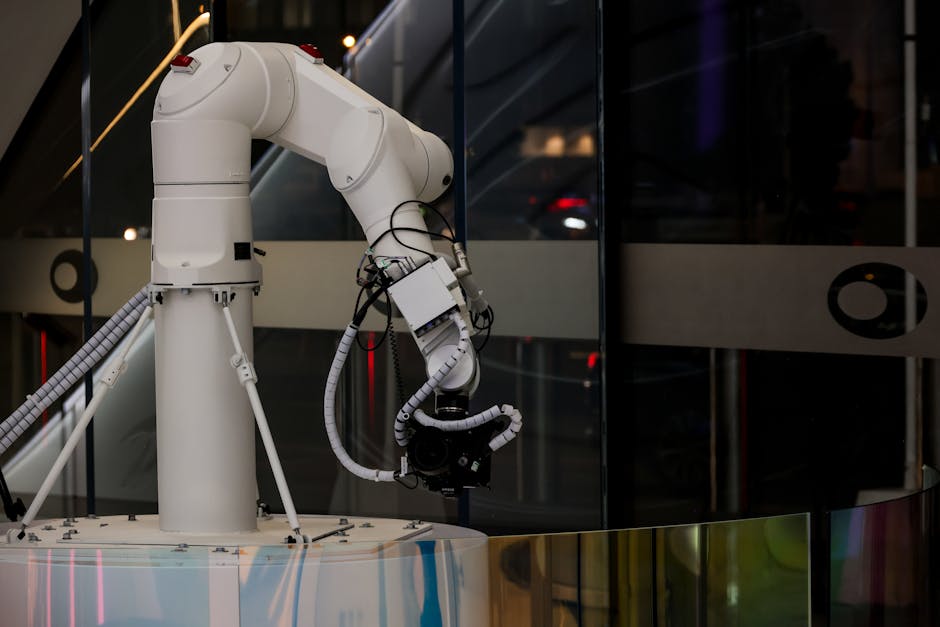

- Physics-based models of every component (fluid dynamics for cooling systems, thermodynamics for furnaces, mechanics for robotic arms)

- Real-time data sync (latency <1 second for some use cases)

- Validation that the simulation actually matches reality (not just “looks plausible”)

I’m not entirely sure why the industry pushes digital twins so hard when most factories would get more value from just fixing their data pipelines and running basic anomaly detection. My best guess is that “digital twin” sounds futuristic and justifies big consulting fees. But if you’re a startup or a small manufacturer, focus on the low-hanging fruit first: get clean data, build simple models, prove ROI. You can build a digital twin later.

What AI Can’t Do (Yet)

AI is great at pattern recognition, optimization within defined constraints, and prediction when you have good historical data. It’s terrible at:

- Handling truly novel situations. If a failure mode appears that’s not in your training data, the model will either miss it or hallucinate a wrong answer.

- Explaining why something happened. A neural network can tell you “this bearing will fail in 2 days” but not “because the lubrication system has been running 5% below spec for three weeks.” (We’ll cover explainable AI later in the series, but it’s still limited.)

- Integrating cross-domain knowledge. A maintenance technician with 20 years of experience knows that a specific sound from a compressor means the inlet valve is sticking, even if the sensor data looks normal. Encoding that kind of tacit knowledge into a model is really hard.

The best deployments I’ve seen use AI as a decision support tool, not a replacement for human judgment. The model flags potential issues, a human investigates, and over time the model gets better as you feed back the human’s labels.

Where to Start

If you’re looking at AI for your factory and don’t know where to begin, pick one high-impact, narrow problem. Don’t try to build a fully autonomous smart factory on day one. Good starter projects:

- Visual quality inspection for a single product line (if you have 1000+ labeled images)

- Predictive maintenance for one critical machine (if you have historical failure data)

- Energy consumption forecasting (if you have a year of usage data and want to optimize time-of-use rates)

Run a 3-month pilot. Measure real business metrics (defect rate, downtime reduction, cost savings), not just model accuracy. If it works, expand. If it doesn’t, figure out why—usually it’s data quality, not the algorithm.

And be prepared for the fact that deploying AI in a factory is 20% modeling and 80% engineering: building data pipelines, handling edge cases, integrating with legacy systems, training operators, managing model drift. The Kaggle leaderboard doesn’t prepare you for that.

Next Up: Computer Vision for Quality Control

In Part 2, we’ll go deep on vision-based defect detection. I’ll walk through training a CNN on real-world factory images (not clean benchmark datasets), handling class imbalance, deploying to an edge device, and debugging when the model fails in production. We’ll also talk about data augmentation strategies that actually work for industrial images—because rotating a photo of a circuit board by 90 degrees doesn’t create a realistic training example.

For now, the key takeaway: AI in manufacturing is not magic. It’s pattern recognition on sensor data. If you have clean data, clear labels, and a well-defined problem, it works. If you don’t, fix the data pipeline first. The fanciest deep learning architecture won’t save you from garbage in, garbage out.

Did you find this helpful?

☕ Buy me a coffee

Leave a Reply